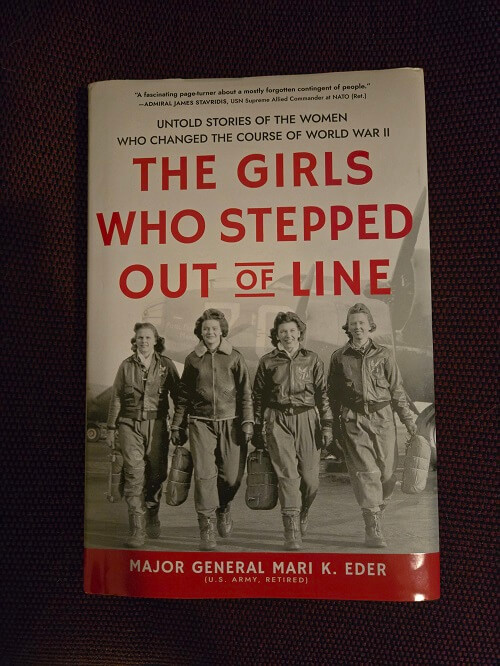

The Girls Who Stepped Out of Line: Untold Stories of the Women Who Changed the Course of World War II (Major General Mari K. Eder)

In this non-fiction book, Eder tells the stories of multiple women who were pilots, smugglers, partisan fighters, etc. In this book review, I will concentrate on two women’s stories.

Chapter 1: Wonder Woman

Alice Marble, an international tennis star, was in Switzerland in 1945 playing in tennis exhibitions and visiting with old friends and a man she called Hans Steinmetz (not his real name) with whom she had been involved with in the past. Alice had fallen in love with Hans, but she didn’t love him enough to marry him.

Back in the U.S., she’d fallen in love and married a man who, unfortunately, made her a widow. When she returned to Switzerland, she resumed her relationship with Hans, but it was a planned ruse. She was now working for U.S. Army handler, Major Al Jones. When she left a party at Hans’s mansion, Major Jones followed her and pulled her over to the side. She told him she had the camera with the film that she had stolen. Stepping out of Al’s car, a man with a Russian accent demanded the camera. At that moment, she realized Al was a traitor. She screamed, “You bastard” to his face. The camera fell to the ground. Alice turned and ran. Behind her, she heard squealing brakes, doors slam, and gunfire. She felt pain and fell to the ground.

Alice woke up in an Army hospital in Germany. She was told by Colonel Linden that Al had shot her. He said, “We had to kill him and the Russian before anyone else showed up. But before he died, he opened the camera. Alice, I hate to tell you this, but the film was ruined. We lost everything. All the evidence is gone.”

After hearing this, Alice sat up,” I can still help you,” she said, “I have a photographic memory, and I can recall every name on the list and the exact amount of every deposit listed in the bank leger.”

A year later, Alice was watching a news reel. The names and amounts of the deposits were read out one by one at the Nuremberg trials. Her evidence had made an impact.

Chapter 5: The Limping Lady

Virginia Hall, having furthered her education in Paris and Vienna, wanted to enter the diplomatic service, but she was turned down because she was a woman. She eventually took a job at the U.S. embassy in Warsaw in 1931. Two years later, she had a new job in Smyrna, Turkey. She wanted to advance, but she didn’t have the patience and wasn’t particularly interested in her job.

Unfortunately, she had an accident with a shotgun that resulted in an amputation. Once she recovered enough to travel to the U.S. to recuperate, she found adjusting to her prosthesis was difficult.

However, Virginia was determined. In 1934, she got a position with the State Department at the American embassy in Venice. In Venice, she applied for the Foreign Service, but she failed. That was the second time she had not passed. When she applied for the FS the third time, she was rejected because of her disability.

When World War II began, Virginia took a job driving an ambulance in France. She also had a part-time job at a newspaper. After France fell to the Nazis in 1940, Virginia went to London where she met George Bellows. He was impressed with her and offered to give her the number of a friend. This led to her becoming a spy in Vichy, France. She was a reporter for the New York Post. She filed stories for the Post, and she embedded coded messages for her London bosses. She ran safe houses and established an “underground railroad” to help downed Allied pilots and former POWs escape to Britain.

In November 1942, one of her contacts put a copy of a Gestapo poster that looked like her under her apartment door. Frightened, she left and linked up with a few Resistance members and guide. Before she departed, she sent a message to Special Operations Executive, letting HQ know her situation.

The only way not to be captured was to go through the snow-covered Pyrenees mountains and cross into Spain undetected. Once they crossed the border, Spanish officials demanded to see their papers, which they didn’t have. They were put in jail, but the American embassy intervened, and they were released in six weeks.

Viginia requested to be trained as a radio operator. The SOE sent her to London where she began to operate the wireless and learn the Morse code. During this period, she was recruited to work for the U.S. Office of Strategic Service. She returned to the Haute-Loire region in south-central France. She disguised herself as an elderly milkmaid, dying her hair gray, and wearing multiple layers of clothing to make her look stout. Her mission was focused on intelligence support for the upcoming D-Day invasion. She roamed pastures and fields trying to keep eyes out for Nazi troop movements, etc.

After dark, she and her team went out in the fields to coordinate drops and arms. Using a wireless radio powered by an old car generator, Virginia would tap messages while a young Resistance member would pedal a reconstructed bicycle recharging the radio’s battery.

After the war, Virginia received the Distinguished Service Cross. The DSC is the Army’s second highest reward for heroism. The French government awarded her the Croix de Guerre avec Palmen.